I skip the Rio beaches for a trip to the trash yard where I make some surprising finds, like genuine hospitality and an enormous will to survive.

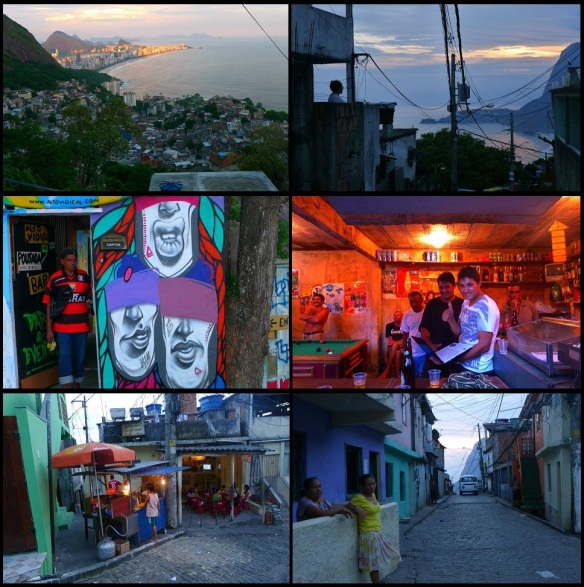

Rio de Janeiro, a beautiful, unique metropolis where green and concrete go hand in hand like nowhere else. I am in the land of samba and beaches, carnival and suntanned bodies lingering around the seaside. Sounds great, and it is – but I want to discover something else, the reality that lies behind the hills, beyond Christ the Redeemer’s reach. Out in the suburbs, where most of the people really have to struggle to make a living. I venture into the depths of the Rio outskirts, to Gramacho, Rio’s biggest trash yard, where thousands of people make a day to day living by scavenging trash.

Leaving the highway, I find the typical taverns empty and the pavement replaced by gravel. A burning rash pit tells me that I’m getting closer. Next to the biggest stack of cans I’ve seen in my life, an old lady is digging through a pile of garbage. Shacks and huts are the only constructions besides huge industrial warehouses.I’m here.

I get there in the mid afternoon, and the stench of mixed waste immediately invades my nostrils. A security guard comes to tell me that I am not allowed to go in. After a brief bureaucratic conversation with the yard manager, I’m informed that I need a special permit to visit the premises. Frustration kicks in. Now that I have made it to Rio, now that I have come this far, I cannot accept returning empty-handed. The security guard, meaning well, suggests I visit the slum right next to the yard instead, but he immediately regrets it. “You really shouldn’t go there, it’s too sinister.” Literally, that is the word he used. But I decide to ignore his advice and head for a small hut made of bare bricks and sticks that seems to serve as a tavern. I figure that this is where I can find people who work on the trash yard.

I get there in the mid afternoon, and the stench of mixed waste immediately invades my nostrils. A security guard comes to tell me that I am not allowed to go in. After a brief bureaucratic conversation with the yard manager, I’m informed that I need a special permit to visit the premises. Frustration kicks in. Now that I have made it to Rio, now that I have come this far, I cannot accept returning empty-handed. The security guard, meaning well, suggests I visit the slum right next to the yard instead, but he immediately regrets it. “You really shouldn’t go there, it’s too sinister.” Literally, that is the word he used. But I decide to ignore his advice and head for a small hut made of bare bricks and sticks that seems to serve as a tavern. I figure that this is where I can find people who work on the trash yard.

A young toddler, not more than three years old, approaches me with a curious smile. He starts grabbing my pockets, laughing and trying to play with my camera. He is followed by his dad, sporting a suspicious look. “E ai cara! What’re you up to?” I introduce myself, shake his hand and reply that I’m just curious about the place and would like to talk to people that make a living trash scavenging. At first, Fabinho is understandably cautious, not talking too much. We order beers, we chat for a bit and I tell him about my city, which makes his eyes wide with curiosity. Suddenly he just tells me: “Ai cara, I’ll show you everything you need! You just need to follow me.”

I decide to believe him, to award him the trust and  optimism I have gotten travelling by myself. Fabinho has been working here for 15 years. He used to be involved in “illegal businesses” which I decide not to ask about. “At least I’m not out on the streets, robbing people. Here you can make the basic. What it takes to survive. Not more, not less. But I’m not getting into trouble.” He taps me on the shoulder and shakes my hand once again, in a way to reassure himself. His calloused, hard hands have a strong grip that makes me look him straight in the eye and smile. We understand each other. We continue through the back streets, meandering around, talking to other “catadores.”

optimism I have gotten travelling by myself. Fabinho has been working here for 15 years. He used to be involved in “illegal businesses” which I decide not to ask about. “At least I’m not out on the streets, robbing people. Here you can make the basic. What it takes to survive. Not more, not less. But I’m not getting into trouble.” He taps me on the shoulder and shakes my hand once again, in a way to reassure himself. His calloused, hard hands have a strong grip that makes me look him straight in the eye and smile. We understand each other. We continue through the back streets, meandering around, talking to other “catadores.”

Then, we reach this yard where everybody is frantically busy, digging through the trash. Nearby, a pig is having a feast and a bunch of roosters get the scrapes. “In a few months, vai virar assado!” The pig continues eating, oblivious to the fact that it will find itself on the barbecue soon. We walk around and I talk to some of the other scavengers. What really strikes me is that these people are proud to keep their dignity. Proud to be making a legit living, based on a system where people are paid for each kilo of plastic, metal or cardboard they bring. In a city where easy money seems to be a temptation, working here is seen as something valid.

I ask Fabinho if he feels like he was contributing to society in general. After all, he is responsible for a massive amount of recycled material every day. His answer is simple: “I think I am, but cara! That’s not why I do this! I can’t read, I can’t write… but I know about things! In the middle of this waste I can always survive… Just the other day, I found a cell phone and that gave me enough for a whole week! “

I ask Fabinho if he feels like he was contributing to society in general. After all, he is responsible for a massive amount of recycled material every day. His answer is simple: “I think I am, but cara! That’s not why I do this! I can’t read, I can’t write… but I know about things! In the middle of this waste I can always survive… Just the other day, I found a cell phone and that gave me enough for a whole week! “

That said, we go back to the tavern. We order pinga com mel, Brazilian sugarcane booze with honey, and we drink. After the first sip, Fabinho tells me: “Cara, I don’t do this to any gringos normally… But you came here and shook our hands, you played it cool…so, I showed you around.” I must look like a child, so wide is my smile that it begins at one ear and finishes at the other.

I can only thank him for the “honor,” for his priceless help and for lifting the curtain to a reality that I was a total stranger to. I return to the city still processing what I have seen and heard. And how a stranger like me was so welcomed to such a different reality, such a degree of poverty and such a will to survive. But, at the same time we were able to communicate and to treat each other as men. As human beings.